|

This first third of Tolkien's saga shows how a young, distinctly unheroic hobbit called Frodo Baggins (Elijah Wood) comes into possession of a ring, reluctantly passed on to him by his uncle Bilbo (Ian Holm). The ring can make its wearer invisible, but also has the potential to wreak universal havoc (it has been likened by some commentators to the nuclear bomb). It attracts the interest of a good wizard gone to the bad, Saruman (Christopher Lee), as well as the ring's original maker, the Satanic figure Sauron, who dispatches nine Ringwraiths to hunt it down. |

| Frodo is warned by a friendly, Merlinlike wizard, Gandalf (Ian McKellen), to carry the ring to safety in the elves' land, Rivendell. Hobbits are not inherently adventurous, being around three foot six in height (a fact delightfully rendered by the use of body doubles and special effects) and more inclined to run than fight. |

| Frodo and his three hobbit friends (Sean Astin, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan) escape the Ringwraiths, with the help of a mysterious human called Strider (Viggo Mortensen) and a beautiful elf-maiden, Arwen (Liv Tyler). But they soon discover from the elf lord Elrond (Hugo Weaving) that the ring is not safe even in Rivendell. |

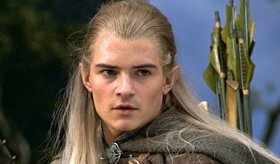

| It must be carried to the very centre of Sauron's empire, Mount Doom, and destroyed. A fellowship to achieve this is formed of the six original travellers, plus Legolas the elf (Orlando Bloom, pictured), Gimli the dwarf (John Rhys-Davies) and Boromir, a nobleman (Sean Bean). Various adventures of this mistrustful alliance ensue, on mountains, in the mines of Moria, in the realm of the elf-witch Galadriel (Cate Blanchett) and beyond, which show Frodo that the ring is even more frightening than he thought… |

|

| A landmark in cinema, an awesome feat of imagination and cinematic daring. Peter Jackson's adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's classic is as near to perfection as makes no difference. The decision to shoot wholly in New Zealand is inspired. Here is landscape photography of a grandeur and emotional resonance that we haven't witnessed in the cinema since John Ford revolutionised the western, and David Lean took to the desert in Lawrence of Arabia. |

| The movie has a mythic grandeur, and a profound understanding of human corruptibility, that makes the Star Wars movies look like kids' stuff. The epic battles and huge set-pieces are as impressive as anything in Braveheart or Gladiator, but the human dimension is never lost, nor a sense of humour. |

| The performances are flawless. Tolkien has been accused of writing one-dimensional characters, but the actors give the lie to that. Two of our most talented theatrical knights, Sir Ian McKellen (as Gandalf) and Sir Ian Holm (as Bilbo), are inspired by their roles to give their finest, most multi-faceted performances on film. |

| It comes as no surprise that Christopher Lee exudes magisterial menace as his rival, Saruman. But actors who have hitherto failed to take the critics by storm - such as Viggo Mortensen as Aragorn and Sean Bean as Boromir - also demonstrate an unexpected degree of nuance and intensity. These are the performances of their lives. |

| Elijah Wood's English accent is excellent, but even more importantly every reaction of his as Frodo, the reluctant hero, seems full of truth and spontaneity. |

| Although I enjoyed the leading performances in Harry Potter, few are in the same class as the ones on offer here. Chris Columbus's film deserved acclaim as a magical experience for children, and solid entertainment for adults. But The Lord of the Rings is an altogether higher achievement. |

| A loving adaptation by Jackson, his wife Fran Walsh, and first-timer Philippa Boyens ensures that, although Tolkien's tale has been shortened (Tom Bombadil, for example, has bitten the dust), not a single major theme has been lost. Diehard Tolkien purists may object that the professor's archaic language has been toned down a little, but this strikes me as justified on grounds of clarity and accessibility. The books are not without their stilted passages and pomposities, and the movie is in some respects an improvement. |

| The two least Tolkienesque remarks - Gimli's indignant "Nobody tosses a dwarf!" and Aragorn's final cry for revenge "Let's hunt some orc!" - succeed in generating the biggest cheers from the audience, and don't detract from the film's essential grandeur and seriousness. |

| Even the most boringly obsessive of Tolkien nerds is likely to find little, if anything, to dislike; and even if you didn't care for the Professor's books, you should still thrill to the movie if you have any feeling for myth, narrative, landscape or cinema. |

| Peter Jackson's direction shows wonderful flair. It is his skill at moving the camera that makes a classic action sequence of the Ringwraiths' chasing on horseback of Arwen and Frodo. |

| The mines of the ruined dwarf kingdom Moria are awesomely designed to look like cathedrals of stone, but the directorial touch that really makes them stick in the sub-conscious is to send orcs - misshapen goblins with serious dental hygiene problems - scuttling down the pillars like cockroaches. |

| The effects are at their most special when they are least obvious - reducing Elijah Wood (5'6") to Frodo Baggins (3'6"), and shrinking Ian Holm to half the size of Ian McKellen. |

| Cate Blanchett as the elf-witch is photographed with an ethereal glow that perfectly complements her finely judged, slightly threatening performance. Even smaller moments of awe, such as Gandalf's firework display at Bilbo's birthday party, are richly imagined and superbly realized. |

| The New Zealand tourist authorities must prepare their country to be invaded by the rest of the world, for every landscape is magnificent. |

| Hobbiton in the Shire is cosy without being twee, the epitome of an English village yet just slightly strange. Some may find the elvish paradise of Lothlorien kitsch - it undeniably owes a lot to Busby Berkeley musicals and the Midsummer Night's Dream of Max Reinhardt - but it's as breathtaking in its way as the darker images which dominate the film. |

| The film faithfully reflects the book, in that it does contain scenes of extreme violence. Tolkien survived the trenches of World War I but saw virtually all of his childhood, teenage and university friends perish. Those images haunted him for the rest of his life, and contribute to the emotional power of his battle scenes. |

| The combination of horrible monsters and violence might well give young or nervous children nightmares, and I personally wouldn't encourage a child of under eight to see it. But I took two boys of ten to its first preview. Both sat riveted for its three hours, pronounced it infinitely better than Harry Potter, and asked immediately when they could see it again. |

| Though it contains all the traditional thrills of a "boys' film", the females are far from ciphers. Liv Tyler as Arwen makes an immediate impact as a heroine, with one of the movie's most exciting chases and the only love scene. Cate Blanchett is superb as the shimmering elf-queen Galadriel. |

| More than any other action-adventure I can recall, the film works as a movie about relationships. The grandfatherly bond between Gandalf and Frodo, the growing cameraderie between the four journeying hobbits, the racial enmity turning to mutual respect of Gimli the dwarf and Legolas the elf, all add texture and human interest. |

| There is a sense that these adventures are more than just a parade of awesome set-pieces. Each climax triggers the emotional growth of the characters. |

| The movie does spectacular justice to Tolkien's love of landscape, which is more than just some vague nostalgia for a pre-industrial England: it also represents a deeply-felt disgust at environmental pollution, that marks him out as decades ahead of his time. |

| The corrupted wizard Saruman's felling of trees and ruination of his own land for warlike purposes is marvellously depicted by Jackson, with the nightmarish grandeur of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. |

| Tolkien was famously modest about his intentions, even claiming that he was more interested in the languages he had created than in his own story. But because he was so steeped in northern mythology, he himself became a master of gripping narrative. |

| Although his trilogy was published in the mid-Fifties, he wrote the books over the pre-war and post-war period. Many of his concerns are the same that made George Orwell write two very different fantasy novels at much the same time, Animal Farm (1944) and 1984 (1948). |

| Tolkien was a conservative Catholic, not a Socialist; but he shared Orwell's fascination with the corruptibility of human nature, and the horrific attractions of totalitarianism. This is the ideological engine that drives the trilogy, and Jackson makes it admirably clear. |

| On the evidence of this first part, The Lord of the Rings is likely to become the most successful movie trilogy of all time, surpassing even Star Wars. But its achievement is artistic, not merely commercial. And there has been no more memorable rendering in cinema of that most uncomfortable and eternally relevant of truths - that power corrupts. |

| It missed out at the Oscars, but still managed to collect an impressive number of technical awards: Best Visual Effects, Makeup and Cinematography. |

|

The extended version (208 minutes):

|

On the DVD, the extended version of the movie runs 30 minutes longer than the original, at just under three and a half hours; and the additional footage has been very skilfully integrated, at no cost to the pacing of the movie or its production values. There is no sense of padding, and Howard Shore has extended his Oscar-winning score and brilliantly embellished it.

|

The extra scenes and bits of scenes add considerable charm and humour - especially early on, with Bilbo Baggins's brief explanation of what makes hobbits tick, principally their passion for food, ale and pipeweed.

|

There's a greater sense of lyricism and foreboding, particularly in the lovely sequence where Sam and Frodo watch elves passing through the woods of the Shire on the way to the Grey Havens of death.

|

The tense relationships between the reluctant monarchist Aragorn and the fiercely republican Boromir and between elves and dwarves are deepened.

|

Perhaps most surprisingly, some of the action sequences are improved - Peter Jackson and his editor seem to have been more inspired at the second attempt even than they were at the first. The battles in the mines of Moria and with the Uruk-Hai at the end are now doubly thrilling.

|

|

|