|

|

| Tookey's Review |

|

| Pro Reviews |

|

| Mixed Reviews |

|

| Anti Reviews |

|

| Cast |

|

| |

|

| |

| Released: |

2002 |

| |

|

| Genre: |

ROMANCE

COMEDY

|

| |

|

| Origin: |

US |

| |

|

| Colour: |

C |

| |

|

| Length: |

0 |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

A screenwriter agonizes over adapting a book that can’t be adapted.

|

Reviewed by Chris Tookey

|

|

Adaptation is the eagerly awaited follow-up to director Spike Jonze and writer Charlie Kaufman’s engagingly eccentric Being John Malkovich. Adaptation is even more bizarre, and in an age when most movies seem to have been made by and for the mentally challenged, it fizzes with joy in its own intelligence and creativity.

|

|

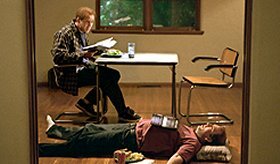

The story juggles playfully the real with the fictitious. The central character is screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (played by Nicolas Cage, pictured left), who – in common with most writers – is self-obsessed, arrogant yet lacking in self-confidence. “Do I have an original thought in my head?” he worries.

He wonders if his time might not be better spent learning Chinese or playing the oboe – anything, in order to avoid having to write, or (worse still) suffer the embarrassment of having human relationships. He is especially mortified by his lack of status on the set of the movie he wrote, Being John Malkovich. None of the actors recognises him, and he is constantly in the way.

|

|

The fictitious Charlie, just like the one in real life, leaps at an offer made by a film producer (Jonathan Demme in real life, Tilda Swinton in the movie) to adapt a (real) non-fiction book, The Orchid Thief, by an equally real New Yorker journalist Susan Orlean (played by Meryl Streep).

|

|

As in real life, Charlie agonizes for months over how to adapt the book. The leading character is Florida orchid poacher John Laroche (another real person, here played by Chris Cooper), and the book attempts to understand the nature of his passion for orchids.

|

|

Both the real and fictitious Charlie do their research and come to the conclusion that the appeal of orchids has something to do with their inspiring ability to adapt in order to attract insects that will enable them to propagate.

|

|

Charlie also spots a hint of sexual attraction in Susan Orlean’s attitude to her hygienically and dentally challenged but charismatic anti-hero. She admires Laroche’s passion for orchids and his adaptabilty. And she wishes she had more of those qualities herself.

|

|

But these ideas are hardly dramatic or gripping enough to sustain an entire screenplay, and the fictitious Charlie (like the real one) tries to back out of the project after six months, on the grounds that there’s no character development, no action and no drama.

|

|

Early on, he has told Swinton’s movie executive that he’s attracted to the project because it doesn’t involve sex, guns, conflict, chases or people overcoming terrible obstacles – in other words, all the mainstays of Hollywood movies. Midway through the movie, Charlie realises that because his screenplay lacks all these things, it is unfilmable.

|

|

At this point, Charlie’s twin brother, Donald (also played by Nicolas Cage, pictured right), comes to the rescue. In real life, Charlie doesn’t have a brother although he mischievously credits him with co-writing his screenplay, which means that for the first time an entirely imaginary person has been nominated for an Oscar.

|

|

For the first part of the movie, Donald acts as comic relief. He’s all the things Charlie isn’t – lithe, confident, attractive to women. He finds writing film scripts annoyingly easy, mainly because he hasn’t an original thought in his head and adheres ruthlessly to the principles expounded by real-life screenwriting guru Robert McKee (wonderfully impersonated by Brian Cox).

|

|

There are several funny scenes where Donald tries to get creative help from a querulous Charlie, who can’t believe how crass and derivative his twin brother’s ideas are. Humiliatingly for Charlie, Donald’s first screenplay is snapped up by Hollywood.

“It’s Silence of the Lambs meets Psycho” says Donald; “Oh,” says Charlie, compressing a lifetime of anger, distaste and hopelessness into one syllable. The ebulliently optimistic Donald encourages the creatively constipated Charlie to attend a three-day seminar by McKee.

|

|

Slumped hopelessly in McKee’s audience, Charlie loathes the tutor’s attempt to reduce screenwriting to formula. Charlie points out to the great man that in real life nothing much happens, people don’t have epiphanies, nothing changes. McKee tells him that if he doesn’t put these things in his screenplay, “you’ll bore the audience out of its mind”.

|

|

“You can not have a protagonist without passion,” McKee barks. “God help you if you use voice-over,” he snarls, badmouthing one of Charlie’s most treasured devices.

|

|

And McKee warns the desperate writer against resorting to plot mechanics in the final act that are too convenient to ring true: “Don’t you dare bring in a deus ex machina!”

|

|

Perversely inspired by McKee’s instructions and helped by his more intrepid twin Donald’s investigative abilities, Charlie discovers a final act for his movie, which I shall not reveal, except to say that it has nothing to do with reality but involves sex, drugs, guns, a chase, and an alligator as “deus ex machina”.

|

|

Some people don’t like the denouement and feel it’s a Hollywood cop-out, but I loved it. It brilliantly captures the ambivalence of most professional writers. You want to express yourself and put across your ideas, yet at the same time you want to reach an audience.

|

|

The real Susan Orlean is understandably pleased with Kaufman’s adaptation, even though Kaufman has invented a very different Susan Orlean to suit his purposes. In one of the best performances of her career, Meryl Streep attacks the part with gusto, showing us an icily elegant, ruthless New York journalist discovering the sleazy swamp rat within her – adapting, in other words.

|

|

The whole film is a pun on its title. Charlie Kaufman has to adapt to being an adaptor. He even finds out, like the adaptable orchid, how to make contact with the opposite sex, thus turning the movie into, among many other things, a romantic comedy.

|

|

Adaptation communicates the central ideas of Orlean’s book, but it does so in a totally unconventional manner that both imitates and satirises Hollywood convention. Adaptation is as funny as Being John Malkovich, but displays a deeper understanding of human nature, particularly about the way people accumulate emotional baggage as they get older, and become decreasingly willing or able to adapt.

This is a wise, entertaining, exquisitely crafted comedy, enlivened by consistently witty visuals by Kaufman’s collaborator, Spike Jonze. Cage is hilarious in both roles, and Chris Cooper is marvellously charismatic as the orchid thief.

|

|

Adaptation will appeal especially, though not exclusively, to anyone who writes, or wishes to write. It is not for the stupid or humourless, and will strike some people as too clever by at least three-quarters. But I haven’t emerged from a screening so uplifted and excited for a long time. This is a marvellously rich, original movie, with a screenplay of genius.

|

|

|

|

|